This article was originally published on Fool.com. All figures quoted in US dollars unless otherwise stated.

Between March 2000 and October 2007, the S&P 500 Index (SNPINDEX: ^GSPC) increased by a rather paltry 1.43%. To compound that painful six-and-a-half-year period, the S&P would fall more than 55% from the 2007 high during the Great Recession.

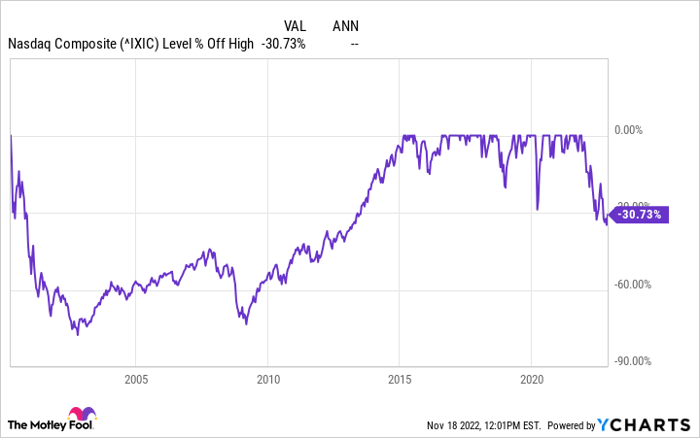

Combined, the world's most notable stock index -- a collection of 500 of the most-valuable and important public companies on earth -- would lose more than half its value in the "lost decade" between March 2000 and March 2009. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite (NASDAQINDEX: ^IXIC) would lose nearly three-fourths of its value over the same period.

The S&P would take another four years to return to the highs it reached in 2000, while the Nasdaq didn't fully recover until March of 2015. That's 12 and 15 years respectively for these two indices to fully recover.

Fast-forward to today, and investors are fearful that we could be near the start of another lost decade, particularly for tech investors. Is that the case? With rising interest rates and economic pressures changing the game from the cheap-capital, grow-grow-grow days of the past decade, the recent pain could continue for many beaten-down tech stocks for some time to come.

But there's more to the story. If you want to avoid the mistakes that likely cost likely millions of people billions in lost wealth, keep reading.

How we got here

The broad stock market downturn we've seen this year only tells part of the story. The S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrials (DJINDICES: ^DJI) peaked in January of 2022 and are down 18% and 9% respectively during a painfully long downturn for stocks this year. The Nasdaq Composite peaked in November of 2021 and is down 31% at recent highs.

So far, these drops are a far cry from the near-75% wipeout from the dot com crash. This time around, the most-valuable tech stocks have, relatively speaking, held up much better. Microsoft, for example, has seen its stock fall about 30% from the recent highs, while it lost more than 60% of its value during the dot com bust, and it was still off more than 70% from the high in March 2009. Similarly, Apple shares fell more than 60% in the dot com crash, though the success of the iPod and iPhone during the years of the Great Recession changed its prospects -- and stock price.

Today, these multi-trillion-dollar tech stocks are massive, stable companies, and that's helping buoy the Nasdaq in ways that index wasn't supported following the 2000 peak. But when we peel back the layers, we see the pain: More than 1,600 of the nearly 4,200 Nasdaq-traded stocks are 50% or more below their 52-week highs. More than 1,100 Nasdaq stocks have lost more than twice as much value as the Nasdaq Index.

As a result, plenty of investors who've focused on smaller, high-growth companies in recent years saw their portfolios lose massive amounts of value over the past 18 months or so.

What it means going forward -- and the biggest mistake to avoid

Let's be honest with ourselves: Many of those stocks won't fully recover to their prior highs. A lot of unprofitable businesses were able to raise money in an environment where interest rates were low, bond yields were paltry, and plenty of investors were willing to pay premiums and take on more risk to capture returns. Some of those companies won't be able to make the transition from money-burning to profitable, at least without taking actions that further impair per-share returns. A lot will get acquired for less than investors paid for them, with no better options on the table.

But for investors, anchoring on what you paid for a stock, or what it was worth at the peak, won't help you invest better, make up for losses, or build future wealth. But there is some wisdom we can take from looking at the market's history. Let's look past those prior peaks, and consider how stocks did in the periods in between:

Don't make the mistake of getting caught in up past stock price peaks, and walk away from stocks during the sell-off. Investors make their best money continuing to buy during downturns, when everyone else is afraid it will get worse.

Just keep buying

This is the hard, cold, reality of investing in stocks: In the short term, you can lose money (at least on paper); and sometimes, you can lose money for longer than you expect. This is particularly true during the moments of peak exuberance when markets are near a peak, and recent market gains bring stock buying back into the popular consciousness -- at least for a time. Then interest wanes as stock prices falter, and the rush for the exits results in big losses, burning a lot of people and turning them off from stocks entirely.

Instead of avoiding that risk, investors can make that an advantage. It's during these downturns that investors make their money: Find the companies that can still deliver on their long-term goals, buy, and hold.

It sounds simple, and to some extent it is. But it's not easy. Living through and investing during painful downturns is hard. But as those sharp gains after every prior downturn should remind us, it's very profitable. And that makes it another hard thing that's worth doing well.

This article was originally published on Fool.com. All figures quoted in US dollars unless otherwise stated.